So in recent years I’ve become a bit of a history fanatic.

Weekday meals? 30 minutes of Youtube documentaries for lunch. 1 hour for dinner.

Reading list? At least half are history books.

Odd few minutes here and there? I’ll be exhausting the question library on another history quiz app.

We’ll come back to this obsession of mine soon. Meanwhile, it has led me to conclude a timeless truth.

That history is just a collection of narratives and metanarratives.

And all of us perceive reality through narratives.

Of course, not all stories are an accurate representation of the objective truth.

Regardless, one cannot deny that storytelling is humanity’s most effective vehicle for transmitting perspectives. It has for thousands of years, and will continue to be for many more.

But the structure of all narratives falls on a spectrum of psychological vs sociological.

The implications in recognizing this distinction extends well beyond historical interpretation.

It flows into how we see the world. Our role in it. As well as how we choose to interpret what happens in our lives.

So, what do we mean by psychological and sociological narratives?

1. Psychological vs Sociological Narratives

Psychological narratives are about individuals. Sociological narratives are about systems.

Psychological narratives captivate the audience with a compelling character. Sociological narratives usually have a wider cast of characters that come in and out of the narrative.

Psychological narratives dramatize the struggles of the protagonist. Sociological narratives dramatize the incentives of a system.

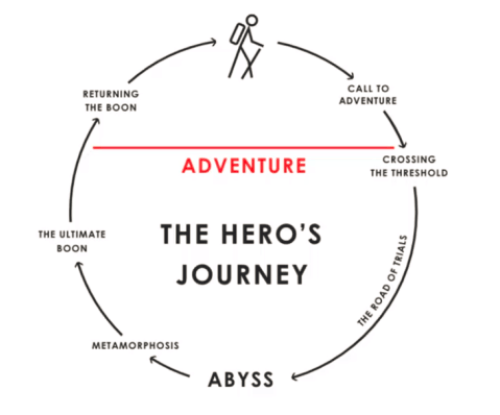

People enjoy psychological narratives because they get attached to the characters. The character development and transformation of the protagonist is celebrated. The blueprint of such a story is follows the Hero’s Journey:

This timeless archetype is the reason why many psychological stories seem so familiar. From Greek tragedies to Shakespearean dramas, and now Hollywood. The same story is repackaged and retold in a new context. From Lion King to The Matrix, Harry Potter to Lord of the Rings:

See full graphic here.

Meanwhile, people enjoy sociological narratives because it reveals ugly (and beautiful) truths about the world around us. It’s a critique of a social system.

A system is a network of interconnected relationships combining to form an emergent whole. A family is a system. A school is a system. A corporation is a system. Capitalism is a system. The law is a system etc.

Every system contains its own set of rules and incentives. Characters in sociological stories are usually just actors playing out and following the (often) flawed incentive structures of a social system. They merely follow the paths of least resistance in the socially reinforced expectations of that system.

Like a colony of ants, the individuality of the character is less important in sociological narratives. Because if they were replaced with another and put in the same situation, the character would take the same actions.

This is not to say that characters in sociological narratives aren’t able to have individual motivations or agency. They are still able to test the boundaries of the system, often being punished for doing so.

And every now and then, characters manage to change the system itself.

In a way, the ‘hero’ that undergoes a transformative journey in sociological stories is not the protagonist but the system itself.

Some examples of sociological narratives and the systems they critique:

The Big Short. Critique on the laissez-faire capitalism. (It breeds greed and leads to destruction)

Billions. Critique on modern power structures. (Abuse of power comes from both public and private domains)

Contagion. Critique on modern healthcare system. (World is not prepared for a pandemic)

Wall-E. Critique on post-capitalist consumerism. (Humanity can overcome the ugly by-products of capitalism by working together)

Game of Thrones. Critique on government structures. (Benevolent dictatorships don’t work).

Foundation Series by Isaac Asimov. Critique on societal evolution. (Collective societal forces play a bigger role than individual forces on shaping the outcome of humanity).

Of course, most stories lie on a spectrum of between the two. It doesn’t have to strictly be one or the other.

Rule of thumb: whenever there’s no clear main character, the story is probably more sociological than psychological.

Side note. A repeated cheap trick producers turn to when ideas run dry on a sociological narrative is to turn it into a psychological one. But this tends to diminish the quality. The plot becomes preoccupied in petty drama between characters. The show divorces from its original merit as a sociological critique. Psychologist Tufecki wrote a viral essay arguing that this is why fans hated the last season of GoT.

2. Psychological narratives reinforce an individualistic worldview

The simplicity of the Hero’s Journey certainly makes for an elegant psychological narrative. For children and adults alike. A clear villain makes the tension between good and evil come alive. They’re an easier story to tell. This is why movies and TV shows skew more towards psychological rather than sociological. And also the reason why several film adaptations of Foundation, Isaac Asimov’s landmark sci-fi series, have been unsuccessful.

But this popular psychological portrayal reinforces an individualistic worldview. A system is reduced to a collection of individual agents each making their own choices.

People do what they are. Bad people do bad things because they are innately bad. Injustice is an outcome of the isolated actions of a few ‘bad apples’ in society.

This worldview downplays the role of social systems in our world.

Success is by-product of an individual’s character.

In contrast, sociological narratives are built on the premise that we are part of a system larger than ourselves.

Success is a by-product of the individual’s place within the system.

Outcomes can be predicted by just looking at the rules of the system. Characters predictably follow the paths of least resistance.

Take the board game Monopoly for instance. A psychological worldview will conclude that people are inherently greedy. But in a sociological lens, the individual values of the players are irrelevant. Greed is a necessary condition, a requirement, just to participate and play by the rules of the game.

“Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcomes” – Charlie Munger, Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman

Anyone familiar with complexity and systems thinking would say that psychological narratives highlight the characteristics of the node. While sociological narratives highlight the structural relationships between nodes.

“The dynamic relationship between individuals and social systems is what makes social life happen.” – Allan Johnson, sociologist

3. Great-Man vs Macro interpretations of history

Back to my history obsession.

A friend of mine, let’s call him Sam, shares this passion for learning history.

However, the ways that we approach history stand on two opposite extremes.

Sam immerses himself in biographies.

He meticulously studies the extraordinary lives. The freak few that made an irreplaceable dent on the human story. If they didn’t exist, the world would undoubtedly be a different place. Political leaders, generals, founders, scientists etc. From Washington to Deng Xiaoping. Aristotle to Keynes. Newton to Darwin. Rockefeller to Musk.

Here, historical narratives are told through the lens of an individual. Timescales span several decades. In line with the lifetime of the individual.

My appetite, on the other hand, prefers a broader, more macro lens of history. Typically stretched over longer time frames.

I’m less concerned with the lives of specific individuals, and more interested in the broader sequence of events.

For instance, I’d compare the expansion patterns of the Ottoman and Roman empires. Rather than comparing the stories of Mehmed and Caesar. And I find myself indulging in macro flavored videos like these:

Here, historical narratives are told through the lens of a system that typically transcend character and place. Timescales span several centuries. More like the lifetime of an empire, or a historical epoch.

Put simply, Sam tends to interpret history psychologically. While I interpret it more sociologically.

So if one was to ask: How much do leaders influence the outcome of history?

Sam would answer, “a lot more than people think”. This is the “Great-Man” view of history. Named after British historian Thomas Carlyle who asserts that the world is shaped primarily by the decisions and actions of a few “great men”.

While I’d be answer, “a lot less than people think”. This reflects a more macro interpretation of history. In line with Russian author Leo Tolstoy, who asserted that leaders have a minimal influence on the course of history. In his novel War and Peace, the orders given by generals are irrelevant to what actually happens on the battlefield.

Another parallel to the psychological vs sociological distinction can be found in computer games. RTS (real-time strategy) games like Age of Empires, Starcraft, Warcraft in particular.

A ‘macro‘ strategy, as they call it, focuses on gathering resources and overwhelming the opponent with a superior army. A larger and more technologically advanced army that’s quickly replenishable, thanks to the backing of solid economy. A sociological paradigm.

A ‘micro‘ strategy, focuses on the movements and positions of the units themselves. More of the player’s time and attention are given to clicking and controlling individual units to gain an advantage. This is much like having the best generals with the best battlefield tactics, executed to perfection. A psychological paradigm.

Of course, the best players balance the two.

4. Implications

Now that we understand the distinction between psychological and sociological narratives, there are a number of lessons to draw. Beyond interpreting history and computer games.

Four generalizable lessons:

(i) Be wary of the our natural tendency to over-emphasize psychological narratives

The world is full of narratives. Society tells us narratives. We interpret reality through a collection of narratives. We tell others narratives. There are narratives we tell ourselves.

Most narratives tend to be more psychological.

Growing up we were fed hero-villain narratives. Thanks to Disney and Hollywood. Business stories glorify or demonize founders and CEOs. Political stories take this to another level with political leaders.

This increases our tendency to overplay the role of our individual actions, and downplay the role of the systems we’re a part of.

And this tendency usually manifests by underestimating the role of good luck when we’re successful: “I’m awesome.”

As well as underestimating the role of bad luck when something goes wrong: “I suck.”

Therefore:

“Be careful who you praise and admire.

Be careful who you look down upon and wish to avoid becoming.” – Morgan Housel, Psychology of Money

Focus less on specific individuals and case studies and more on broad patterns.

“Studying a specific person can be dangerous because we tend to study extreme examples – the billionaires, the CEOs, or the massive failures that dominate the news – the extreme examples are often the least applicable to other situations, given their complexity.”

– Morgan Housel, Psychology of Money

We should go out of our way to find humility when things go right.

And compassion when things go wrong.

(ii) View others’ actions with a more sociological lens

Once we practice humility and compassion to ourselves, we should extend this to how we perceive others.

For instance, a colleague makes a mistake and it blows up in your face. Rather than blaming their stupidity (who they are), instead interpret the event as a byproduct of the broader system they’re in right now. Maybe they’re sleep deprived because their new-born baby kept them up. Maybe they never received the proper training they were supposed to get. Etc.

A more extreme version of this is viewing criminals in death row as a tragic byproduct of design flaws in society. Rather than “these people are innately bad.”

Look at the system the individual has been placed in, rather than the individual in isolation.

(iii) View the world through a most balanced lens

To be clear, I’m not advocating that sociological narratives are better or more correct than a psychological one.

But I am advocating for a more balanced view.

Especially if you find yourself more skewed towards preferring one type of narrative.

For example, my conversations with Sam has made me realize that I skew too heavily towards sociological paradigms. I’ve started reading more biographies. And, no doubt, I know that certain individuals do change the course of history.

(iv) Institutional change is difficult but not impossible

A pessimistic interpretation of a sociological is that our fates are at the mercy of the system’s rules. That our outcomes are constrained within the rules of the system.

But systems change. They self-organize. They adapt. They’re antifragile.

Characters within a system have the power to grow and break free. To endeavor through the obstacles of challenging established social norms. To engage with and even rewrite the rules of a system.

History has taught us that changing a system from within is difficult, but not impossible.

This capacity to change the game we’re playing, to self-correct, to upgrade the system, truly accentuates the beauty in this world.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead

Or if you prefer a more optimistic-nihilist ending:

“Life is like peeing into the snow on a dark winter night. You probably made a difference, it’s just really hard to tell.” – Joe Wong, comedian

Found this useful? Can treat me to a coffee 🙂

Or simply share this post with your friends.

Drop your email below for a once-every-few-weeks newsletter packed with a curation of ideas that have kept me up at night.

If you enjoyed this, you may also like:

Common Knowledge: Why I Stopped Avoiding Mass Media